5 powerful nudges that influence human behaviour

Consider the following puzzle:

A bat and ball cost £1.10.

The bat costs one pound more than the ball.

How much does the ball cost?

The number that many people arrive at is 10p, dividing up £1.10 neatly into £1 and 10 pence. However, the correct answer is 5p (if the ball costs 10p then the total cost will be £1.20 - 10p for the ball and £1.10 for the bat).

Now consider another question:

How many animals of each kind did Moses take into the ark?

This question is commonly referred to as the ‘Moses Illusion’. Moses took no animals into the ark; Noah did.

The incorrect answers many people give to these questions offers just a glimpse into the overwhelming evidence that indicates that one of the underlying assumptions of social science, that humans are generally rational and their thinking normally sound, is flawed.

Many of us believe that we know how our mind works, which often consists of one conscious thought leading in an orderly way to another. However, according to the social psychologist Daniel Kahneman, most impressions and thoughts arise in our conscious experience without knowing how they got there. Therefore, the mental processes that produces impressions, intuitions and many decisions goes on in silence in our minds.

The judgements, choices and decisions we make are therefore not always in our complete control. Sometimes we make decisions in the blink of an eye, whilst on other occasions we follow the crowd or co-operate rather than compete. Recent studies have suggested that over 90% of our decision-making takes place in the subconscious mind.

The mental shortcuts people use to form judgments and make decisions are called heuristics and whilst they work under most circumstances, they can lead to systematic errors known as cognitive biases. The theories of heuristics and biases have been used widely and productively in many fields, including government policy, legal judgement, medical diagnosis and finance. However, for a number of years marketers have been experimenting with behavioural science and economics to better understand and change consumer behaviour.

Introducing behavioural economics

The concept of behavioural economics has grown in popularity and prominence over the last decade. Books including Daniel Kahneman’s ‘Thinking, Fast and Slow’ and Richard Thaler and Cass Senstein’s ‘Nudge’ have captured the public’s imagination.

Many of the theories of behavioural economics can be applied to marketing in a different ways and is something Smart Insights have covered before. Ogilvy have even established a specialist behavioural economics practice called Ogilvy Change which employs ‘Choice Architects’ “to investigate and apply principles from cognitive psychology, social psychology and behavioural science to create measurable behaviour change in the real world”.

5 top nudges

Choice architecture is the practice of designing different ways in which choices can be presented to consumers to ‘nudge’ or steer them towards better decision-making. As mentioned above, many of principles choice architects apply have worked in other fields so we thought we’d pick out five nudges, along with examples, that can be applied within a digital marketing context:

Scarcity

What is it?

This is based on the theory that people tend to value things more highly when they believe they are scarce.

Following the lead of many luxury good marketers, Apple, creates the illusion of scarcity to build up the hype of many of its products to fuel desirability and demand. The stories of limited supplies of iPhones and people queuing for days to get their hands on the latest model live long in the memory.

How is this applied in digital marketing?

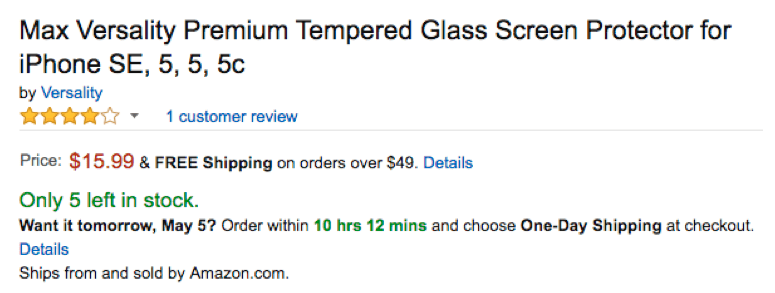

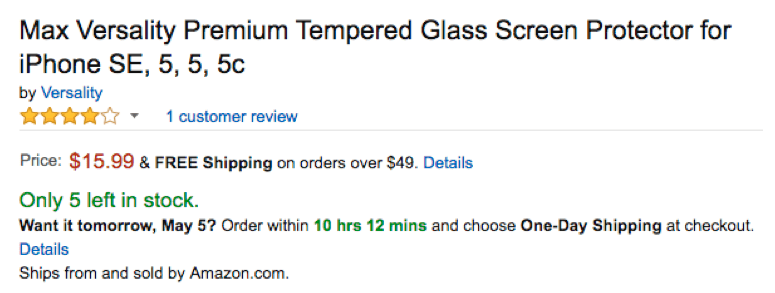

Scarcity and urgency is a tactic that’s commonly used within eCommerce, using messages such as ‘limited availability’ or ‘only X left in stock’:

Source

Source

Using the fear of scarcity to drive demand and sales can be considered to be an unethical and manipulative tactic when used irresponsibly. Scarcity should therefore only ever be used in a transparent and positive way, for example by being honest about what stock is left and whether any more is likely to be made available.

The anchoring effect

What is it?

The value of something is often set by anchors or imprints in our minds, which we use as mental reference points that influence our decision-making. The anchors can be completely arbitrary and still have an impact.

Anchoring is particularly common in situations that involve negotiation. For example, when valuing a house, experiments have shown that the listing price, regardless of the ‘real’ value, can have a powerful effect on someone’s own perception of the value.

Example:

How is this applied in digital marketing?

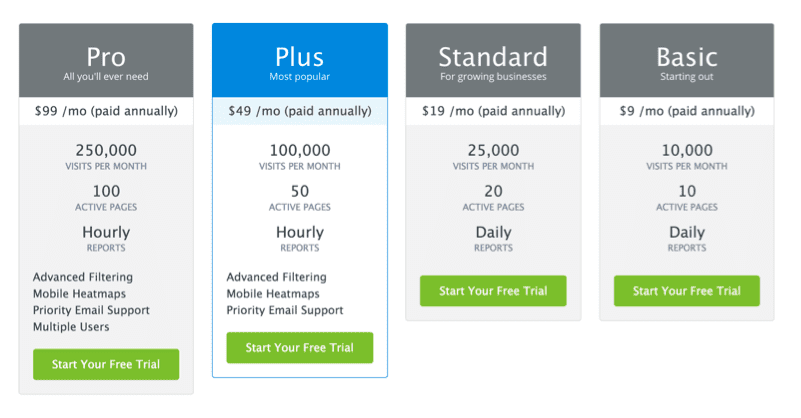

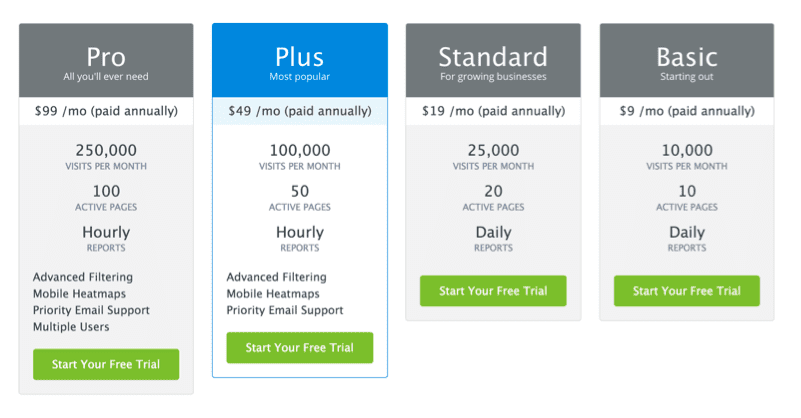

In a digital marketing context, anchoring can be seen in the use of subscription plans:

In this example, we can see the different subscription options for Crazy Egg’s heatmap tracking software. There are two factors at play here:

In this example, we can see the different subscription options for Crazy Egg’s heatmap tracking software. There are two factors at play here:

1. The ‘Pro’ plan is listed on the left where visitors are likely to see this first

2. The ‘Pro’ plan is priced at $99, setting the anchor against which the value of all the other plans (including ‘Plus’, the ‘most popular’ plan) is compared.

Loss aversion

What is it?

We will often go to greater lengths to avoid the loss of something we already have rather than to gain something new. People can find it twice as painful to lose something they own in comparison to how enjoyable it was to acquire it in the first place.

How is this applied in digital marketing?

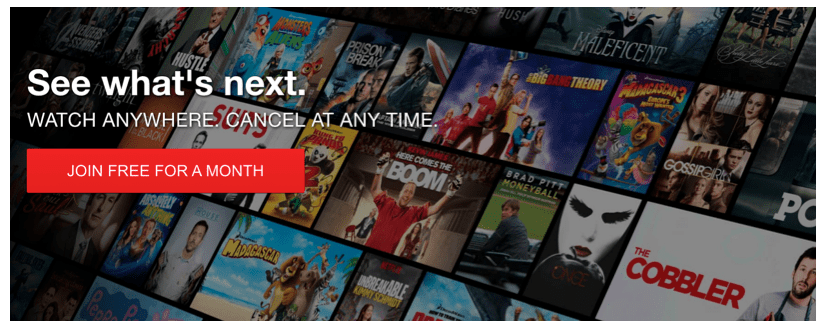

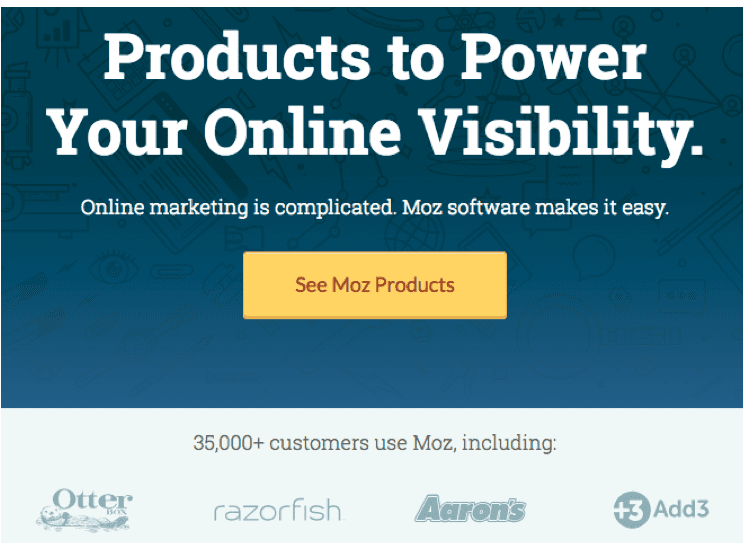

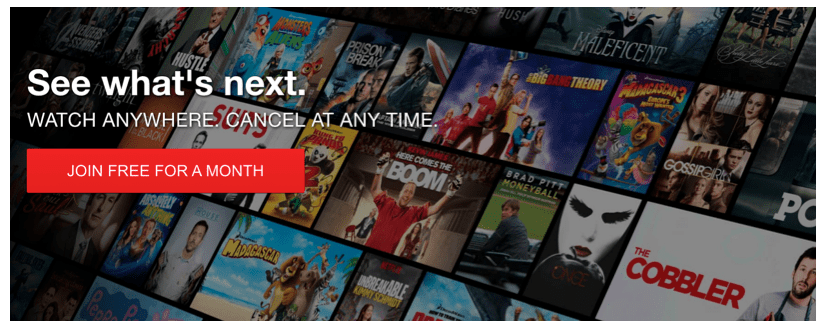

It’s no surprise that many companies, such as Netflix, Moz and Dropbox, offer free trials in order to leverage loss aversion.

By giving prospective customers the opportunity to use a product or service for free for a decent period of time, they begin to feel a sense of ownership. Once the trial period has expired, the thought of losing the product, plus the minimal effort it often takes to sign up and pay, means that many people are convinced to commit to a purchase.

Authority

What is it?

Years of societal convention have led us to place an often irrational trust in the judgment of experts, even if their judgements are not always correct or moral. A famous example of the obedience of authority is the Milgram Experiment, where 65% of people were prepared to administer a 450-volt electric shock to another person hidden from them just because a doctor told them it was OK.

How is this applied in digital marketing?

The practice of brand endorsement by well-known figures such as sports stars, musicians and other celebrities is a perfect example of how authority can be used to influence customers’ decision-making. Much of Nike’s success within the golfing arena is credited with their decision to associate themselves with Tiger Woods, who at the time was the best golfer in the world.

Digital marketers can use authority through the use of thought-leadership, content collaboration and expert analysis to build credibility. As a digital marketing thought leader, Click-Through Marketing utilise Dave Chaffey’s authority on a range of topics.

The paradox of choice

What is it?

Offering customers more choice is not always the best course of action. When we’re paralysed by too many options, the likelihood that we pick the ‘most suitable’ choice is reduced and we procrastinate for fear of making a bad decision. Therefore, when fewer options are presented, there is less chance of making a mistake and decisions are speeded up.

How is this applied in digital marketing?

The paradox of choice is something Smart Insights has covered previously. From an eCommerce perspective, companies like Amazon, Etsy and House of Fraser implement effective filtering techniques to provide the most suitable choices to customers.

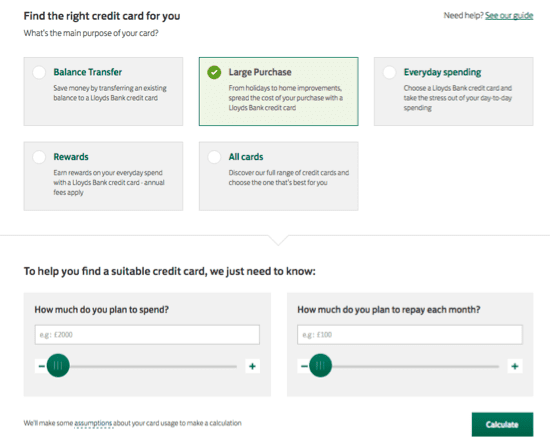

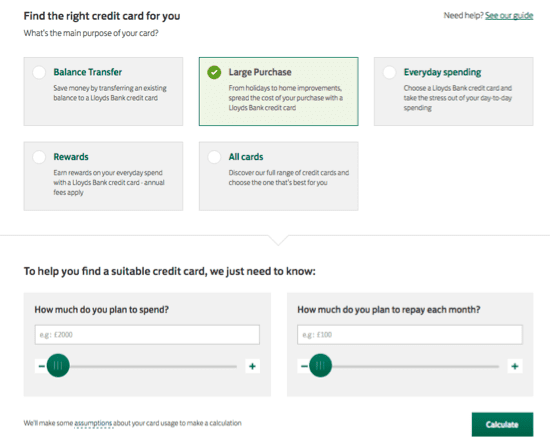

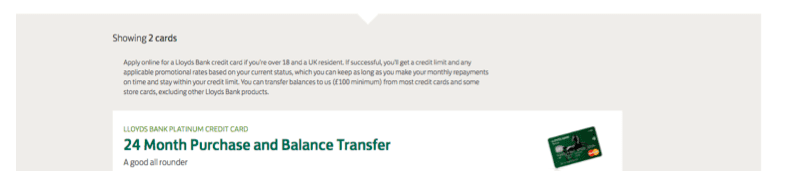

A good use of filtering to optimise relevant results can also be seen in this example from Lloyds:

The bank offers nine different credit cards although a consumer arriving at the site might be a little overwhelmed as to which to choose from. Filtering by the cards by different needs states, in this case Balance Transfer, Large Purchase, Everyday spending and Rewards helps to simplify the number of options and help the consumer choose the right option.

Social proofing/ herding

What is it?

The concept of ‘social proof’ was made famous 30 years ago by psychologist Robert Cialdini’s in his book Influence. Social proof describes our tendency to run with the herd and make decisions based on what those around us are doing. We often validate our choices on whether others were following a similar course of action, which is why books are marketed as ‘bestsellers’.

How is this applied in digital marketing?

There are many different ways to leverage social proof online and data from Smart Insights from 2014 indicates that there is a purchase uplift from tactics such as social sharing and reviews.

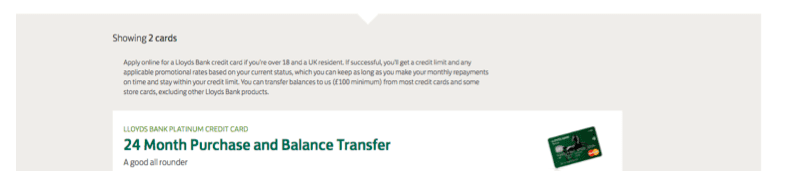

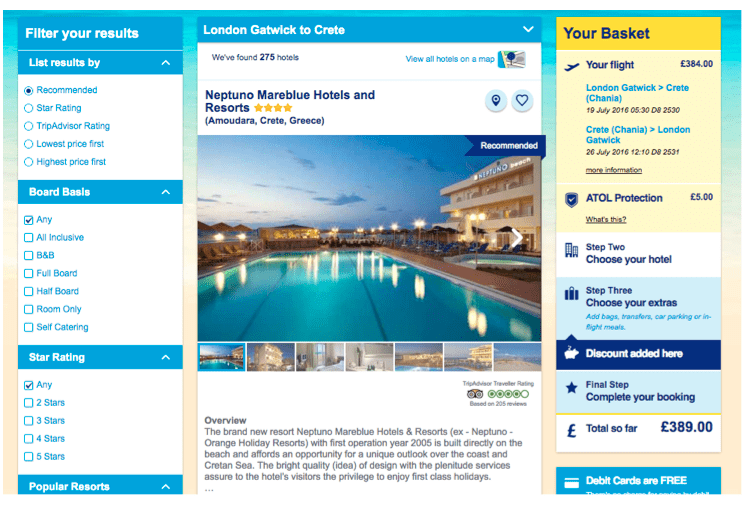

Ratings and reviews are an excellent way to aggregate sentiment from past purchasers and give prospective customers confidence in the products they’re browsing online. They’re particularly effective when sourced from a large population and managed by a third-party, such as this example from travel site On The Beach, which uses reviews from Trip Advisor:

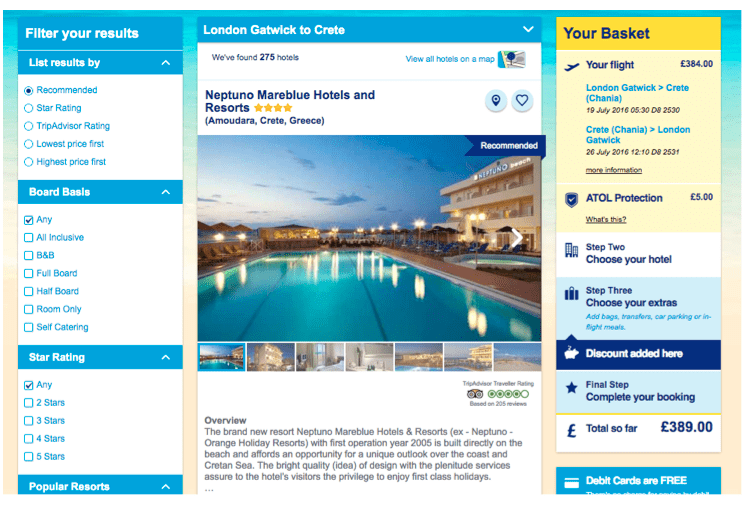

Another popular social proof tactic uses numbers to convince people that a product or service is popular. Moz makes it very clear that their software is used by tens of thousands of companies:

And this popularity is backed up by massive following some of their guides are receiving which supports the authority they have built up in their field of expertise:

Closing thoughts

Many of the principles of behavioural economics can have a powerful and profound impact on consumer decision-making so it’s therefore essential that the nudges highlighted in this post, and the many others that haven’t been covered, are used ethically. There are examples of websites that use manipulative UX practices that exploit consumers’ cognitive biases and this will only ever erode the relationship between the consumer and the brand in the long run. When Richard Thaler signs copies of ‘Nudge’, he always writes “Nudge for good” next to his name and explains that nudging is like giving people GPS: “I get to put into the GPS where I want to go, but I don’t have to follow her instructions”.

Nevertheless, behavioural insights should be considered by digital marketers when crafting strategy as the practices we’ve covered illustrate how marketers can improve the content and overall user experience to improve consumer decision-making and provide better digital experiences.

Marketers can take inspiration from the public sector in how to nudge for good. The government utilised status quo bias, the theory that people prefer to carry on behaving as they have always done, for the UK workplace pensions scheme. Nest automatically enrols employees in a workplace pension yet gives them the opportunity to opt out, resulting in a greater take-up than if employees were required to opt in, which takes more time and effort. Through a subtle change in how the choice is presented, the output results in a win-win for everyone concerned.